ENHANCING SHAKESPEARE:

An exercise in logic, open-mindedness, and Shakespeare

It is not very strange, for my uncle is King of Denmark, and those that would make mouths at him while my father lived give twenty, forty, fifty, a hundred ducats apiece for his picture in little. ‘Sblood, there is something in this more than natural, if philosophy could find it out.

(Hamlet. Act II, scene ii (Q2 version, 1604))

(scroll down)

What it's all about

This website provides an accessible, nonlinear approach to the groundbreaking paper, “A Picture in Little Is Worth a Thousand Words: Debasement in Hamlet and Measure for Measure.”

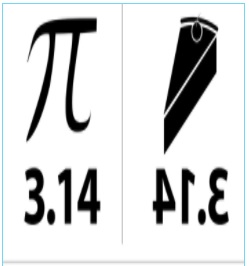

If you are unfamiliar with Hamlet, you will have little problem accepting the paper’s central premise: that Hamlet’s reference to the King’s “picture in little” alludes to the fact that the King’s picture appears on coinage.

If you are familiar with Hamlet scholarship, you might know that editors typically give “miniature portrait” as the meaning of “picture in little.” And yet, coinage is the more logical interpretation at every level: it fits better with Hamlet’s character, Claudius’s character, Shakespeare’s character, and the well-known economic allusions in the rest of the play. And it’s funnier.

Where does this interpretation lead us? First, it supports coin-related solutions to other puzzling lines: If “picture in little” refers to coins, then surely Hamlet’s later reference to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern “soaking up the King’s countenance” does not mean that they are basking in Claudius’s “favorable looks” (the traditional interpretation), but rather that their loyalties have been bought and paid for.

Second, and most important for dramatic purposes, when Hamlet shows his mother two pictures — one of Claudius, one of Hamlet’s father — and compares their attributes in terms suggestive of pure and impure coins, he is most likely showing her coins. This simple explanation cuts through the Gordian knot of conflicting theory (the “pictures” are variously posited as portraits, tapestries, or miniatures; and problems with these interpretations have led some to conclude the pictures are “in the mind’s eye”), and drives home the point of the queen’s subsequent exclamation “This is the very coinage of your brain.”

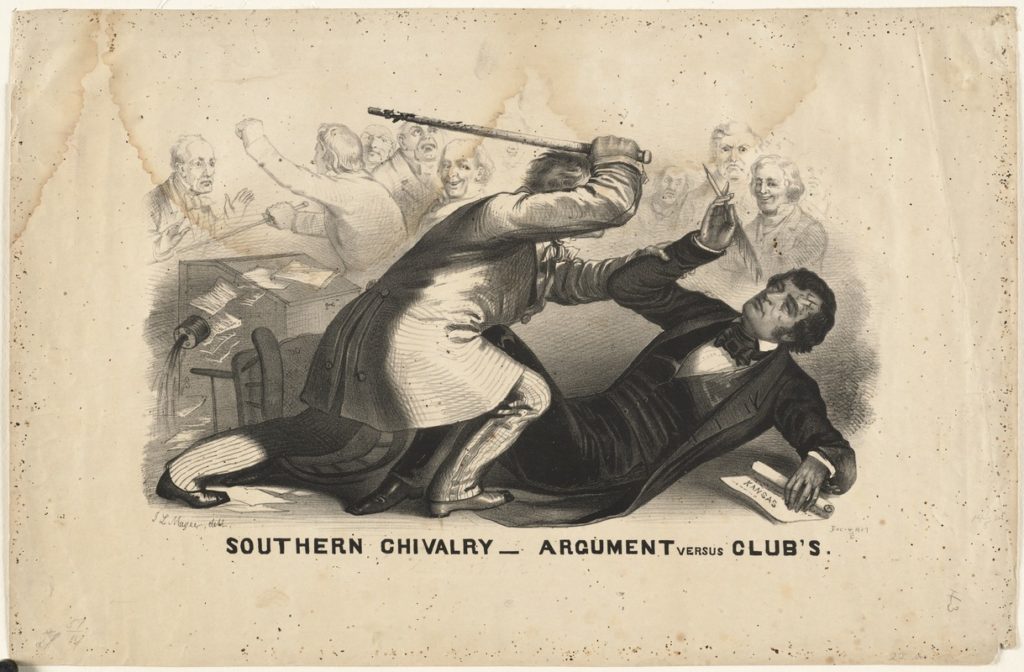

To understand why coins work so well in Hamlet, it helps to understand the debasement metaphor — used in literature at least since the time of Aristophanes. A debased, corrupt coin is used to represent a debased, corrupt person. Shakespeare has done it elsewhere, and he does it again in Hamlet.

The prevalence of the debasement metaphor in Hamlet and other plays leads to some startling conclusions about MeasuRE FOR Measure.

Heroic, regicide promoting, debasement decrying Spanish Jesuit historian, economist, and philosopher.

“I'm convinced, for example, that your suggestion that Hamlet shows Gertrude two coins is far more powerful a stage image than his confronting her with two Hilliard-like miniatures, and will say as much (and acknowledge) when I teach the play again.”

A very well known Shakespeare scholar

“you simultaneously reject many obvious explanations . . . and replace them with your own nonsensical garbage . . . You do this sort of thing again and again, often rolling out blatantly false justifications . . . you must know, that this is a false argument . . you're either lying to yourself or deliberately lying to us. I prefer to think of you as an amiable idiot rather than a cheat, so I'm guessing that you're deluding yourself"

A somewhat less open-minded reader

"Hello. First I want to say that your paper is mind-blowing.

As I think you intended, it gives me faith in the idea that art criticism can be just as rigorous as scientific work. The thesis you argued for seems to mean unquestionable step forward, and I wish it could be even better known."

An intelligent and open-minded reader

“*You* think that what you have done has opened a window to the mind of the great artist Shakespeare that has never been opened before (or at least, if it has, all records of that event have been lost to history). As a result *you* thought that spending hundreds of hours writing garbage was a great way to spend your time."

The same somewhat less open-minded reader